With passive strategies continuing to gather assets at a rapid pace, the “active versus passive” debate remains as pitched as ever. While passive vehicles—in the form of index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs)—are often perceived as attractive alternatives to actively managed products, offering desired market exposure at lower fees and without the risk of significant benchmark underperformance, the reality is more nuanced.

Passive Product ‘Accuracy’ Varies Across Markets, as Do Costs

Passive investments seek to replicate the performance of a benchmark, thereby eliminating one investment risk—namely, the difference between the performance of the market segment and that of the product chosen to represent it. However, not all market segments can be copied with equal precision and ease. More efficient markets—marked by fewer and larger-cap (and thus more liquid) securities—are easier to replicate. Less efficient segments—which consist of more numerous but smaller and less liquid securities—present a greater challenge to the passive vehicle seeking replication.

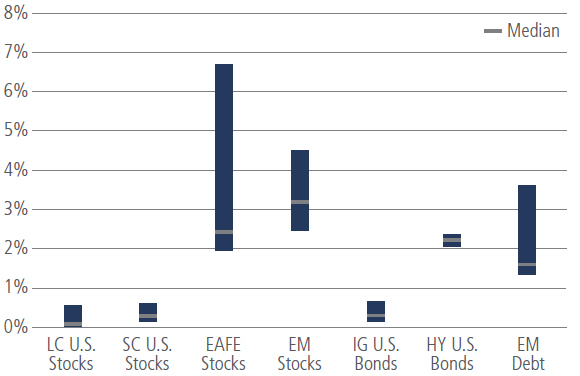

A common proxy for performance dispersion is “tracking error”—the volatility of the difference between the returns of an investment and its underlying benchmark index. As shown in the display below, passive vehicles in some market segments have experienced annualized tracking errors in excess of 2%, a level more commonly associated with active funds and a potential surprise to unwary investors.

Passive Investment Tracking Error Can Be Significant in Some Asset Classes

Five-Year Tracking Errors of Largest Passive Vehicles within Asset Classes

Source: FactSet, Bloomberg, Morningstar, ETFdb. Based on the 10 largest-AUM passive vehicles (index funds and ETFs) within each category. Calculated on monthly data through June 2016. 5-year tracking errors, calculated on monthly data through June 2016, computed against each product’s benchmark.

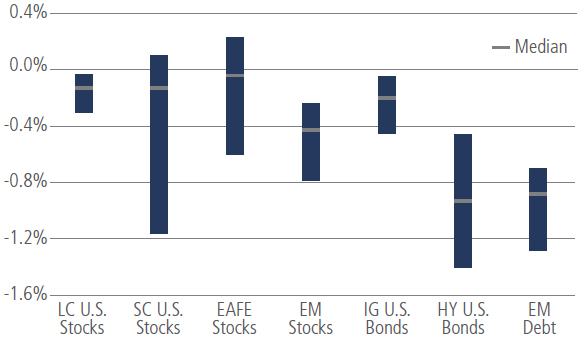

Meanwhile, there is a common perception that passive vehicles are uniformly low-cost. While passive vehicles generally do feature fees and expenses notably lower than their active counterparts, some—namely, strategies replicating less efficient markets—may incur fees and expenses similar to those of active funds, primarily due to trading expenses. Even lower fees have an impact on performance, so the performance of passive vehicles still tends to lag the performance of the index, even if only by a small amount.

Passive Vehicles Have Tended to Underperform Benchmarks After Fees

5-Year Annualized Excess Returns

Source: FactSet, Bloomberg, Morningstar, ETFdb. Based on the 10 largest-AUM passive vehicles (index funds and ETFs) within each category. 5-year annualized excess returns through June 2016, computed against each product’s benchmark.

In our view, low costs in and of themselves are not indicative of any product’s benefit value. Higher fees for active management are due in large part to the investment research and processes that can translate into alpha and/or risk mitigation. To the extent a manager outperforms the benchmark, the higher management fees may be well warranted. On the other hand, for passive strategies, “closet indexers” and/or funds that do not have the potential for outperformance over market cycles, higher fees would not be merited.

Where Active Hits Its Stride

At a basic level, we believe that talented managers across markets have the ability to outperform benchmarks over market cycles. That said, the outperformance potential of active managers is partly a function of the efficiency of the market segment in which they invest. Less efficient, more heterogeneous markets with more sparse analyst research coverage have greater potential performance dispersion among their constituents, enabling active management decisions to have a greater impact on relative return. Likewise, the more decisions a manager makes in constructing a portfolio—e.g., exposure by sectors, countries, currencies, securities, etc.—the more opportunities it has to tilt the portfolio away from the benchmark and potentially drive outperformance.

Overall, academic research has shown that high-conviction active managers (as determined by their active share1) with a long-term focus historically have outperformed their benchmarks net of fees. Lower-conviction, shorter-term focused managers, in contrast, have lagged.2

Risk Mitigation and Other ‘Active’ Benefits

Passive vehicles by design have the same risk profile as their benchmark. Active vehicles, in contrast, may be able to achieve lower volatility than their benchmark while generating superior return/risk ratios. They seek to do so through a variety of strategies and approaches, such as focusing on lower-volatility securities or varying cash levels.

In addition, capitalization-weighted equity indices—i.e., most major benchmarks—by definition capture market momentum; they over-emphasize recent winners, which may have become overvalued, and under-emphasize lagging performers, which may have become undervalued. Naturally, passive vehicles bear these momentum exposures. Active managers, on the other hand, have the potential to mitigate exposure to such momentum trends (including their ultimate manifestation—asset bubbles—which, though infrequent, can have a significant and long-lasting impact on a portfolio (see display)).

Market Bubbles Can Prove Costly

| Crisis | Bubble Sector | Peak Date | Bubble Sector % of Index on Peak Date | Subsequent Sector Performance (Peak to Trough) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dot-com Meltdown | Information Technology | 3/27/2000 | 34.5% of S&P 500 | -82.4% (3/27/2000 ‒10/9/2002) |

| Global Financial Crisis | Financials | 2/20/2007 | 36.5% of Russell 1000 Value | -80.1%(2/20/2007 ‒ 3/6/2009) |

| Oil Price Collapse | Energy | 6/23/2014 | 15.7% of Russell 1000 Value | -49.2%(6/23/2014 ‒ 1/20/2016) |

Source: Bloomberg, Neuberger Berman.

Bond markets present similar risk-mitigation and return-enhancing opportunities for active investors. First, fixed income benchmark allocations typically are determined based on the amount of debt issuance; as such, larger debtors are heavily weighted in index funds, leaving the funds vulnerable to specific credit problems. Puerto Rico (in the municipal market) and the heavily levered energy sector (in high yield) come to mind as issuers to which one may prefer not to be significantly exposed. Second, the current low interest rate environment means that broader fixed income indices (and the index fund and ETFs that seek to replicate them) now carry extremely low yields. Although active managers are affected by this problem as well, they have the ability to exert more flexibility in terms of duration, credit selection and in some cases choice of market to enhance yield and total return potential.

Conclusion: Weighing the Differences

In sum, a thorough understanding of the nature of passive investments is no less important than a thorough understanding of active products. Not all passive vehicles are created equal, and not all market segments lend themselves equally well to efficient, accurate, low-cost replication. Furthermore, even in the easier-to-replicate market segments, the benefits of active management—namely, the ability to add alpha and mitigate risk and undesired factor exposures—must be balanced against the cost difference between active and passive products to truly capture the total value proposition that each presents.

As with any other investment decision, selecting an appropriate mix of active and passive strategies—and the vehicles themselves—requires thorough due diligence and thoughtful evaluation of available options.