The business press is breathlessly speculating about the number of Federal Reserve rate hikes we’ll see by December. But that issue is just a detail compared to what we think will be the real fixed income story of this year, and indeed of the next several years: the transition from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening. We believe that this, the Great Unwind, portends a much trickier road ahead for bond portfolio construction, and also carries very potent implications for overall portfolio volatility management.

From QE…

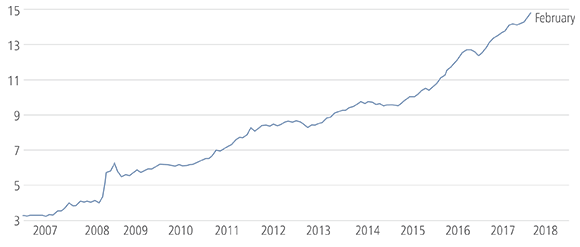

It’s hard to put into perspective just how important the various quantitative easing programs of the world’s central banks have been to capital markets, but let’s start with one number: $12 trillion.

The Great Balance Sheet Buildup

Major central banks: Total Assets (trillion dollars, nsa)

Source: Haver Analytics.

That’s the “stock,” the total increase in assets on the banks’ balance sheets since 2008. But to really appreciate just how this number has impacted asset prices, it’s important to drill down a bit and look at the “flows,” the timing and regularity of the liquidity injections. That’s similarly impressive: On a net basis, central banks added liquidity to world markets every month for 108 months, right up until this past January.

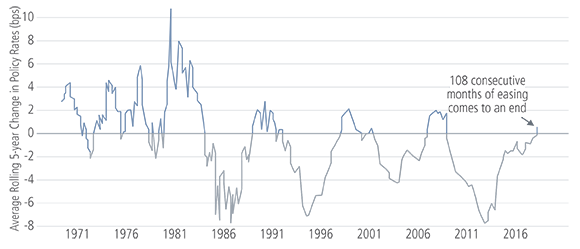

FOMC, ECB and BoE on Average Tightening for First Time Since Pre-crisis

Former 5-year changes in policy rates incorporate Wu-Xia shadow rates

Source: Bloomberg.

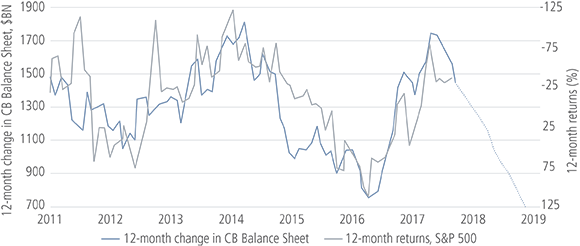

And finally, let’s zoom in on those flows and track the correlations between them and the prices of both investment grade bonds and the S&P 500:

Central Bank Balance Sheet Flows vs. Investment Grade Spreads

Source: Citibank.

Central Bank Balance Sheet Flows vs. S&P 500 Performance

Source: Citibank.

Cumulatively, the various QE programs have been massive; and the liquidity injections have been extraordinarily consistent for many years. Asset prices have responded just as one might expect.

…to QT

But now, not only are the liquidity spigots being shut; the drainage process is beginning. It’s an enormous, artificial and literally unique phenomenon in financial history. So it has not been, and cannot be, factored into traditional investment models and formulas. That’s why fiduciaries must be particularly vigilant about it.

The exact mechanism of QT is worth understanding. The Fed won’t be selling Treasuries (or the collateralized mortgage obligations and similar instruments it bought) to reduce its balance sheet. Instead, it will accept payment of them under their original terms, but then do something rather odd with the proceeds.

And that is: destroy them. Literally. The “money” used to purchase the assets in the QE programs were Fed-created blips; and so to unwind, the money those assets generate will now be Fed-destroyed. This was, by the way, the idea all along; it’s why the Fed could argue that QE wasn’t “money printing” to start with.

The taper actually began last October at the rate of $4 billion per month; and it’s gradually increasing to its projected maximum rate of $20 billion by October. Thus, the monthly inflows from assets purchased via QT will exceed the amounts destroyed each month for a good while; and the Fed will remain a net buyer of bonds until those lines cross, albeit at ever-lower levels.

Of course, this would cause tightening in any market. But we can hardly ignore that the timing here is, in our view, likely to have a sort of double whammy effect: The Treasury will not only be refinancing the old debt it’s paying off, but it will also be borrowing ever more to cover increased larger federal deficits worsened by the recent tax law and budget deal.

Implications for Fiduciaries

Fiduciaries, therefore, are confronting a situation in which rates may well rise faster than would be indicated by growth in economic activity and inflation. And, of course, the Fed is indeed also saying that it will make moves to increase short-term rates via more traditional open market operations. What are the practical implications?

First, the program’s exact mechanics and timing will impact individual bond holdings differently. The always-idiosyncratic nature of bond performance is, we believe, likely to be amplified.

That impact could also be compounded by other simultaneous major policy changes. The newly announced tariffs (and inevitable retaliatory tariffs) and the recent tax legislation are likely to reverberate in ways that create clear winners and losers at both the category and issuer levels.

Unfortunately, standard recipes for dealing with specific kinds of risks in the fixed income market may prove less than reliable in this environment. One example: We take for granted that high yield bonds provide a significant measure of insulation from pure interest rate risk, the most obvious of the fixed income risks today. But those bonds can also be particularly exposed if geopolitical events suddenly push credit spreads wider, or tax law changes fundamentally impact a given issuer’s ability to pay.

So, for fixed income in particular, this is no time for simplistic, “one-size-fits-all” thinking. Active bond managers have already been significantly outperforming passive approaches for several years now; we think that QT and the other policy shifts are very likely to increase that discrepancy. Aside from simply understanding how given instruments may respond to QT, tariffs and taxes, many active managers can pivot between a broader range of instruments, like convertible bonds and floating rate asset-backed securities. And many may also employ more timely and sophisticated strategies, like relative value, in constructing their portfolios.

But we believe that the most profound single implication of QT for fiduciaries is probably this: Plain-vanilla bond portfolios may well cease functioning as ballast for stock market volatility.

Of course, the idea that bonds should insulate portfolios from equity volatility dates back to the early days of modern portfolio theory, and has become utterly ingrained over a five-decade bull market in fixed income. But just as QE ushered in a period where both asset classes rose in lockstep, QT (and the other policy shifts) could send them both the other way. The evidence appears plain: For the first quarter of the year, most major bond and stock indices were down.

So where else can you look to reduce investment risk? First, of course, certain classic styles and sectors of long-only equity investment tend to be more resilient in major downdrafts, such as large-cap value, utilities and defense (which has some particular appeal given the mood in Washington, DC). But, in general, long-only is obviously, by definition, not particularly well suited to portfolio protection.

A classic institutional strategy worth considering within near-dated target date funds or other professionally managed asset allocation strategies is put writing, especially where the premiums are invested in short-term bonds. If the puts are exercised, the writer winds up owning the underlying stock at a better price than the market offers at the time; if not, the premium is simply pocketed. In principle, the approach could over time provide most of the upside of the market with less downside volatility.

We also think that certain specific kinds of hedged strategies—especially long/short and other “equity hedge” styles—may be quite helpful here. This classic risk mitigation strategy, invented by Benjamin Graham back in the Roaring Twenties, remains a solid bulwark against volatility.

One particular sub-strategy to consider now is low-leverage, low-net-exposure funds. These maintain a modest difference between the net-long and net-short positions (say, a couple dozen percent), and do not attempt to magnify their returns by borrowing. Such funds can reasonably be seen as bond-like replacements, designed as they are to generate modest annual gains with limited downside.

Of course, any strategy other than long-only will involve additional costs to operate as compared to a passive choice or standard active management. And cost is always a factor to consider in making investment decisions. But a key fiduciary obligation is to strive for risk-adjusted net-of-fee returns for the portfolio as a whole. So far in 2018, the institutional investors who have embraced less traditional risk-limitation strategies have been rewarded on that net-of-fees basis; and our view is that there’s a good chance that the trend will continue during the Great Unwind.

Conclusion

QT is a fundamental shift that demands reevaluation of portfolio construction, precisely because it has not, and cannot be, accounted for by standard investment formulas and models. Fiduciaries should very carefully consider the exact composition of their bond portfolios; and, just as importantly, reconsider how to best insulate their equity portfolios from volatility if bonds and equities should begin to act less like counterweights and more like twins.